More Information

Submitted: October 04, 2022 | Approved: December 16, 2022 | Published: December 19, 2022

How to cite this article: Kaur H, Arora J, Pandhi N, Arora A. A case of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis complicated by nocardiosis and staphylococcus aureus infection. J Pulmonol Respir Res. 2022; 6: 022-027.

DOI: 10.29328/journal.jprr.1001040

Copyright License: © 2022 Kaur H, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Allergic Broncho Pulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA); Nocardiosis; staphylococcus aureus; High Resolution Computed Tomography (HRCT) Chest; Total serum Ig E titres

A case of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis complicated by nocardiosis and staphylococcus aureus infection

Harveen Kaur4* , J Arora2, Naveen Pandhi3 and Anmol Arora4

, J Arora2, Naveen Pandhi3 and Anmol Arora4

1Senior Resident, Department of Pulmonary Medicine, Government Medical College, Amritsar, Punjab, India

2Senior Resident, Department of Radiodiagnosis, Adesh Medical College, Ambala, India

3Professor and Head, Department of Pulmonary Medicine, Government Medical College, Amritsar, Punjab, India

4Junior Resident, Department of Radiodiagnosis, Adesh Medical College, Bathinda, Punjab, India

*Address for Correspondence: Harveen Kaur, Senior Resident, Department of Pulmonary Medicine, Government Medical College, Amritsar, Punjab, India, Email: [email protected]

Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) is a pulmonary disorder caused by complex immunological reactions to Aspergillus fumigatus [1,2]. High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) of the chest is the imaging modality of choice for the diagnosis of ABPA [3].

Long-term oral glucocorticoid therapy is often required to prevent the progression of lung damage in ABPA [4]. Risk of acquiring secondary infections by organisms like Nocardia; staphylococcus aureus is significantly increased in patients of ABPA, who are on steroid therapy. Nocardiosis should be strongly suspected in patients who are immunocompromised and have features of severe pneumonia with nodular or fluffy infiltrates on the chest X-ray. Accentuation of zonal differences in ventilation and perfusion in ABPA patients leads to susceptibility to S. aureus infection and subsequent damage. Alternatively, S. aureus may have a predilection to occur in the lung with upper lobe damage which coincidentally occurs in both conditions.

Nocardiosis is a life-threatening infection with a protracted course, and delayed diagnosis. We report this case of Nocardia Sp. and staphylococcus aureus co-infection in a middle-aged male patient diagnosed with ABPA, so as to make the treating physicians more vigilant – as an early diagnosis and treatment of Nocardiosis has a better prognosis.

A 45-year-old male presented with chief complaints of breathlessness, cough, and fever. At the time of admission, he complained of increasing shortness of breath for the last 6 days, fever with chills for 4 days, cough with mucopurulent expectoration, and generalized fatigue. He had complained of breathlessness and cough on and off for the past 8 years and experienced more exposure to dust, which is associated with seasonal variation. He took medications on and off from a local RMP, including a prednisolone course three months previously. He was non-diabetic and non-hypertensive. He had no known drug allergies and denied any family history of lung disease or allergies. There was no history of exposure to animals, environmental irritants, or tuberculosis. He was non-alcoholic, non-smoker, no history of tobacco abuse.

On examination, he has a Pulse of 145 bpm, Blood Pressure of 136/84 mm Hg, Respiratory rate of 26/minute, and SpO2 88% on room air. Respiratory system examination revealed bilateral coarse crepitations with rhonchi on auscultation. The rest of the systemic examination was within normal limits.

Initial laboratory evaluation revealed Hemoglobin 10.2 g/dl, WBC 23,890/mm3, B. Urea 36 mg/dl, S. Creatinine 1.1 g/dl. Liver function tests were within normal range. Viral markers for HIV, hepatitis B and C, were non-reactive.

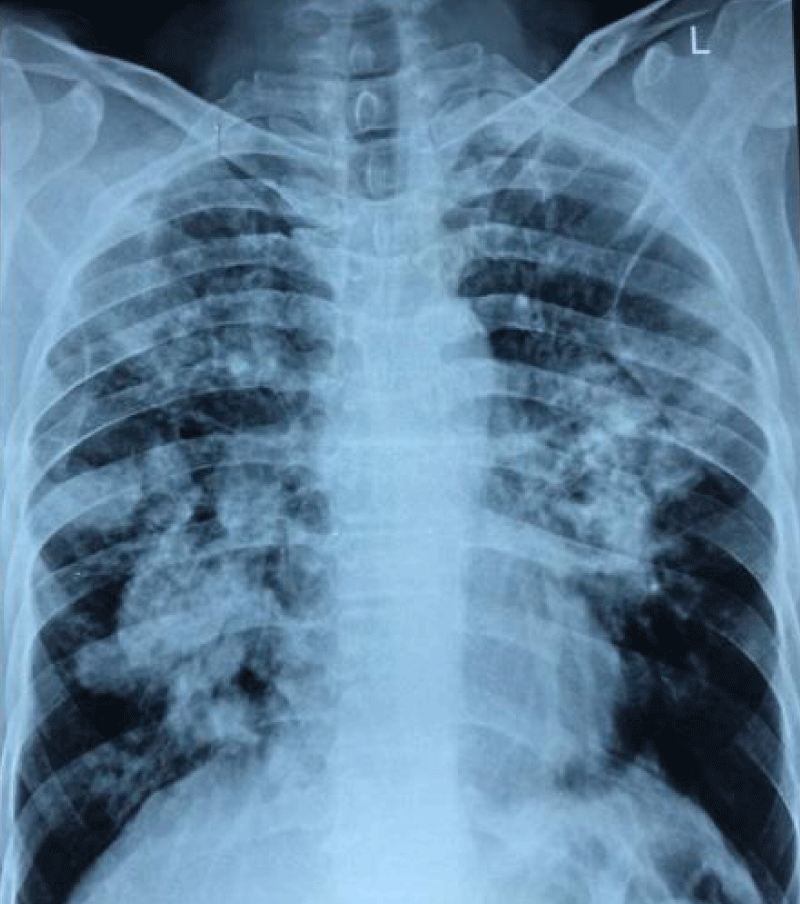

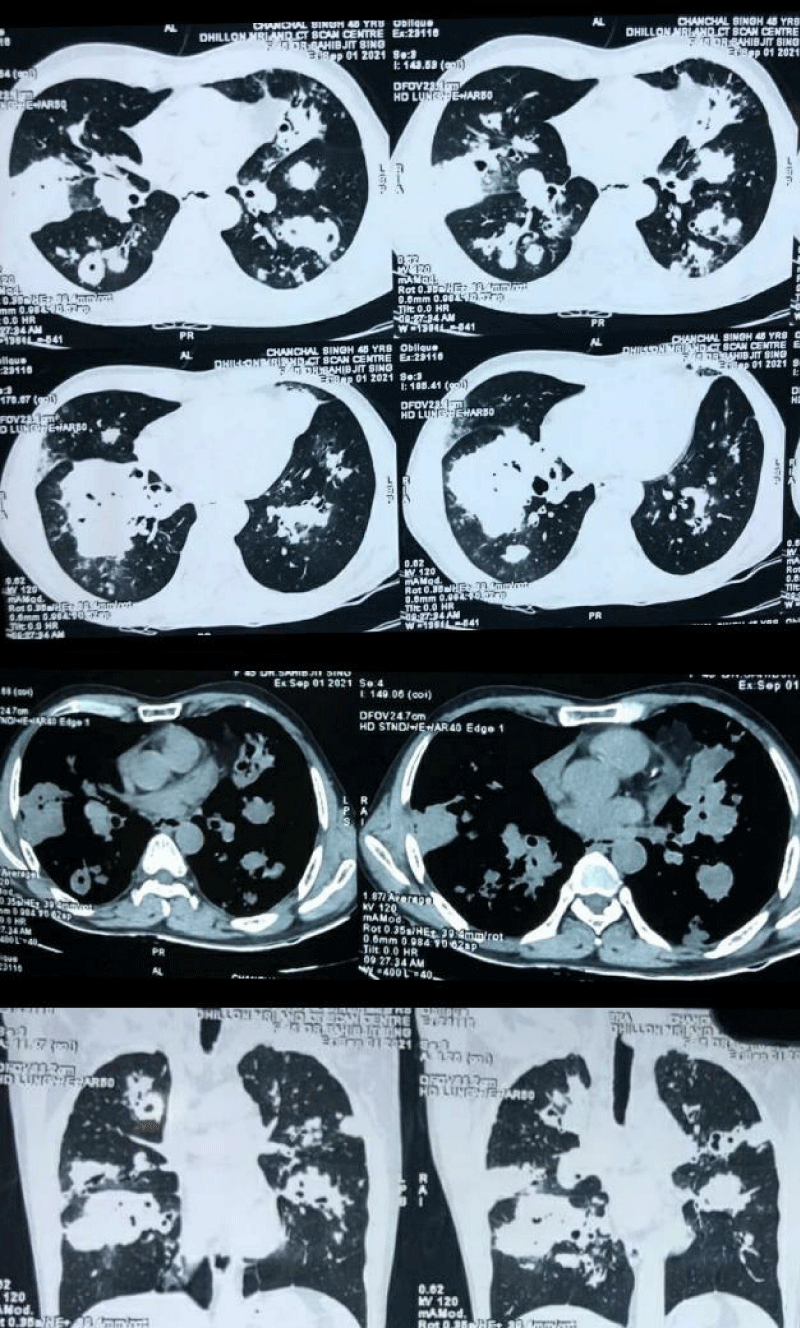

Chest X-ray PA view revealed fluffy nodular opacities in bilateral lung fields (Figure 1). HRCT Chest showed central bronchiectasis changes in bilateral lung fields with consolidative changes showing air bronchogram and formation of bronchomucocele scattered in both the lung fields, along with acinar and acino nodular opacities adjacent to the consolidative changes and few enlarged paratracheal, premarital and subcarinal lymph nodes (Figure 2). The radiological findings were suggestive of ABPA.

Figure 1: Chest X-ray PA view showed bilateral fluffy nodular opacities.

Figure 2: NCCT Chest revealed central bronchiectasis changes in both the lung fields with consolidative changes showing air bronchogram, with adjacent acinar and acino nodular opacities and formation of bronhcomucocele scattered in both the lung fields and few enlarged paratracheal, precarinal & subcarinal lymph nodes, the appearance s/o ABPA.

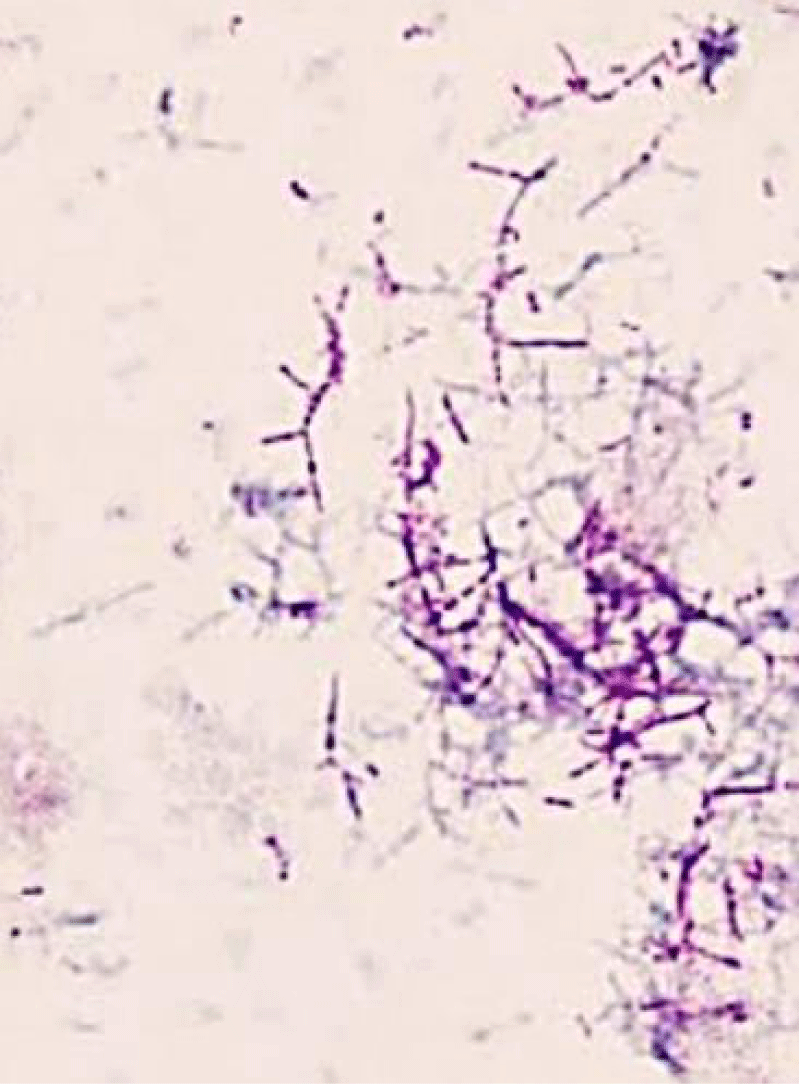

Further laboratory evaluation revealed Total serum Ig E levels of 4892 IU/ml and specific IgE against Aspergillus fumigatus was also positive (20.5 kU/L). The clinical presentation along with serological and radiological findings confirmed the diagnosis of ABPA. Sputum was subsequently sent for microscopic evaluation and bacterial and fungal cultures. It revealed a branching, filamentous, gram-positive rod, weakly positive with a beaded appearance on acid-fast staining (Figure 3). Sputum sample sent for modified acid-fast staining showed Nocardia asteroids. The microbiological culture on the blood agar medium revealed the growth of staphylococcus aureus. He was started on oxygen therapy with a simple oxygen mask and later shifted to a non-rebreather high-flow oxygen mask due to worsening. He was started on injectables: meropenem 1g I.V. TDS, linezolid 600 mg BD, along with glucocorticoid therapy 0.75 mg/kg/day and itraconazole 200 mg BD. He became symptomatically well within two weeks and was advised to follow up after discharge.

Figure 3: Ziehl-Neelsen (Z-N) staining of sputum showing long delicate branched filaments that are weakly acid-fast and beaded pattern suggestive of Nocardia species.

The prevalence of ABPA in asthma varies from 2% to 32% [5]. The condition generally presents with poorly controlled asthma, hemoptysis, fever, and weight loss. The Rosenberg Patterson criteria are most often used for diagnosis [6,7], however there is no clear consensus on the number of criteria needed for diagnosis [8]. The minimum essential criteria for diagnosis of ABPA in asthma are the presence of asthma, immediate cutaneous reactivity to Aspergillus species or Aspergillus fumigatus, an elevated total serum IgE (> 417 kU/l), and elevated serum IgG or IgE to Aspergillus fumigatus. A diagnosis of seropositive ABPA (ABPA-S) can be made with the above criteria [9].

CT Chest is the imaging modality of choice for the diagnosis of ABPA. ABPA can be classified on HRCT chest as serologic ABPA (ABPA-S), ABPA with central bronchiectasis (ABPA-CB) and ABPA with central bronchiectasis and high-attenuation mucus (ABPA-CB-HAM) [10]. While central bronchiectasis (CB) is considered to be a characteristic feature of ABPA, it is not essential for diagnosis, and CB is considered a late manifestation of the disease [11]. The mainstay of therapy is glucocorticoids with anti-fungal agents like itraconazole.

Nocardiosis is an opportunistic infection and occurs in individuals with suppressed cell-mediated immunity. The risk is increased several-fold in people who are on steroids or immunosuppressants [12]. Therapy of ABPA includes long-term steroid therapy along with antifungal drugs, thus predisposing to the development of opportunistic infections. Pulmonary infection is the most common manifestation of Nocardiosis and diagnosis is often missed leading to significant morbidity and mortality. Symptoms include productive cough with thick purulent sputum associated with fever, dyspnoea, anorexia, and pleuritic chest pain. Chest X-ray is non-specific and may show bilateral infiltrates which are dense with nodules that often cavitate. Modified acid-fast staining is an easy way to diagnose Nocardia infection and the microbiologist should be asked to look for Nocardia Sp. in case of strong suspicion. Pulmonary Nocardiosis has a high mortality rate ranging from 14% - 40% and about 60% - 100% in patients with dissemination to CNS [13]. Sulphonamides have been the mainstay of therapy for Nocardiosis. Trimethoprim sulphamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) combination has been usually used for treatment. Combination therapies with cotrimoxazole, amikacin, and cephalosporin or imipenem have been recommended as empirical therapy in serious, CNS and disseminated cases [14].

There exists an association between ABPA and infection with staphylococcus aureus [15]. S.aureus is a gram-positive coccus, which may stimulate an inflammatory response that causes lung damage. Staphylococcal pneumonia is frequently severe and typically occurs in relatively debilitated patients. Predisposing factors are age > 65 years, alcoholism, chronic bronchopulmonary disease, immunodepression, renal failure, and diabetes [16]. Infection with S. aureus in patients with bronchiectasis is more frequently associated with ABPA and is a useful marker for the condition. In ABPA the germination of Aspergillus spores in the airways and continued exposure to fungal elements in combination with specific IgE and IgG antibodies leads to immune-mediated damage of bronchial walls. The long-term sequelae of this process are fibrosis and bronchiectasis which is often in the upper lobes, providing credence to the possibility of a common mechanism rendering these individuals more susceptible to chronic infection with S. aureus [17].

The reported patient had risk factors for Nocardiosis as he was on long-term oral steroid therapy for ABPA. Co-infection with staphylococcus aureus probably further worsened the clinical condition of this patient.

Often, polymicrobial pneumonia is seen in patients of ABPA taking steroids and with underlying lung pathology. Delays in the diagnosis and treatment can be life-threatening. Resistance is an emerging concern and combination therapy is an option in serious and disseminated diseases. This case reinforces the need for testing for Nocardia spp. in patients with risk factors for pulmonary Nocardiosis and pneumonia who have not responded to treatment, in order to reduce the delay in treatment and to prevent the disease progression.

- Agarwal R. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. In: Jindal SK, Shankar PS, Raoof S, Gupta D, Aggarwal AN, Agarwal R, editors. Textbook of pulmonary and critical care medicine. 1st ed. New Delhi: Jaypee Publications; 2010; 947e70.

- Patterson K, Strek ME. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2010 May;7(3):237-44. doi: 10.1513/pats.200908-086AL. PMID: 20463254.

- High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) of the chest is the imaging modality of choice for the diagnosis of ABPA.

- Safirstein BH, D'Souza MF, Simon G, Tai EH, Pepys J. Five-year follow-up of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1973 Sep;108(3):450-9. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1973.108.3.450. PMID: 4126802.

- Agarwal R. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Chest. 2009 Mar;135(3):805-826. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-2586. PMID: 19265090.

- Rosenberg M, Patterson R, Mintzer R, Cooper BJ, Roberts M, Harris KE. Clinical and immunologic criteria for the diagnosis of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Ann Intern Med. 1977 Apr;86(4):405-14. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-86-4-405. PMID: 848802.

- Patterson R, Greenberger PA, Halwig JM, Liotta JL, Roberts M. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Natural history and classification of early disease by serologic and roentgenographic studies. Arch Intern Med. 1986 May;146(5):916-8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.146.5.916. PMID: 3516103.

- Agarwal R. Controversies in allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Int J Respir Care. 2010; 6: 53e4-6e63.

- Kumar R. Mild, moderate, and severe forms of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis: a clinical and serologic evaluation. Chest. 2003 Sep;124(3):890-2. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.3.890. PMID: 12970013.

- Agarwal R, Khan A, Gupta D, Aggarwal AN, Saxena AK, Chakrabarti A. An alternate method of classifying allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis based on high-attenuation mucus. PLoS One. 2010 Dec 15;5(12):e15346. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015346. PMID: 21179536; PMCID: PMC3002283.

- Agarwal R, Khan A, Garg M, Aggarwal AN, Gupta D. Pictorial essay: Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2011 Oct;21(4):242-52. doi: 10.4103/0971-3026.90680. PMID: 22223932; PMCID: PMC3249935.

- Minero MV, Mar´ýn M, Cercenado E. Nocardiosis at the turn ofthe century. Medicine. 2009; 88(4): 250-261.

- Wallace RJ. Treatment options for Nocardial infection in HIV patients. Journal of critical illness. 1993; 8: 768.

- Martínez R, Reyes S, Menéndez R. Pulmonary Nocardiosis: riskfactors, clinical features, diagnosis and prognosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2008; 14: 219-27

- Germaud P, Caillet S, Caillon J, Allenet MC. Pneumonies communautaires à staphylococcus aureus chez des patients adultes non VIH [Community-acquired pneumonia caused by staphylococcus aureus in non-HIV infected adult patients]. Rev Pneumol Clin. 1999 Apr;55(2):83-7. French. PMID: 10418051.

- Shah PL, Mawdsley S, Nash K, Cullinan P, Cole PJ, Wilson R. Determinants of chronic infection with staphylococcus aureus in patients with bronchiectasis. Eur Respir J. 1999 Dec;14(6):1340-4. doi: 10.1183/09031936.99.14613409. PMID: 10624764.

- McCarthy DS, Simon G, Hargreave FE. The radiological appearances in allergic broncho-pulmonary aspergillosis. Clin Radiol. 1970 Oct;21(4):366-75. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(70)80070-8. PMID: 5476800.